Term 1 for 2024 has wrapped up, so it’s a good time to pause and reflect on my practice so far this year.

Supporting Teaching and Learning

Supporting teaching and learning across the school is a vital aspect of the teacher-librarian’s role and helps us showcase our value to our colleagues. During Term 1 I was able to display this in four key ways: first, through supporting the NAPLAN testing running in the library; second, through supporting the ongoing programming, implementation, and resourcing of the new 7-10 English syllabus; third, through the provision of one-on-one senior mentoring and assessment assistance; and fourth, through the expansion of the Teacher Reference collection.

However, reflecting on my practice in this area reveals that there’s more I could be doing to support teaching and learning across other curriculum areas, especially if I wish to raise the library’s profile amongst the teaching staff. I have recently conducted a significant weeding of our non-fiction resources, so could restock this collection with more relevant, updated texts to support current teaching units across the school. At the moment my information literacy and research skill lessons are one-off bookings, so I could also approach different faculties to embed these skills into their assessment tasks, or create pathfinders to support staff as they guide students through the research process.

I’ve previously put out surveys to my colleagues asking for feedback on what they teach and what resources they’d like to see from me, as well as asked staff to send me their assessment notifications so I can support their faculties with informative displays and assessment help. However, staff responses are always limited, revealing that when teachers are under the pump and feeling the pressure of heavy workloads they’re unlikely to prioritise such surveys even if they see their value. It therefore might be more effective to visit different staffrooms in person, either by attending different faculty meetings or by booking in time with each Head Teacher to see how best I can support the teaching and learning in their specific curriculum areas. I could also use this time to promote our Teacher Reference section, which isn’t getting much love from our time-poor staff.

Action moving forward: Speak with Head Teachers in person to determine how I can support teaching and learning in their faculties.

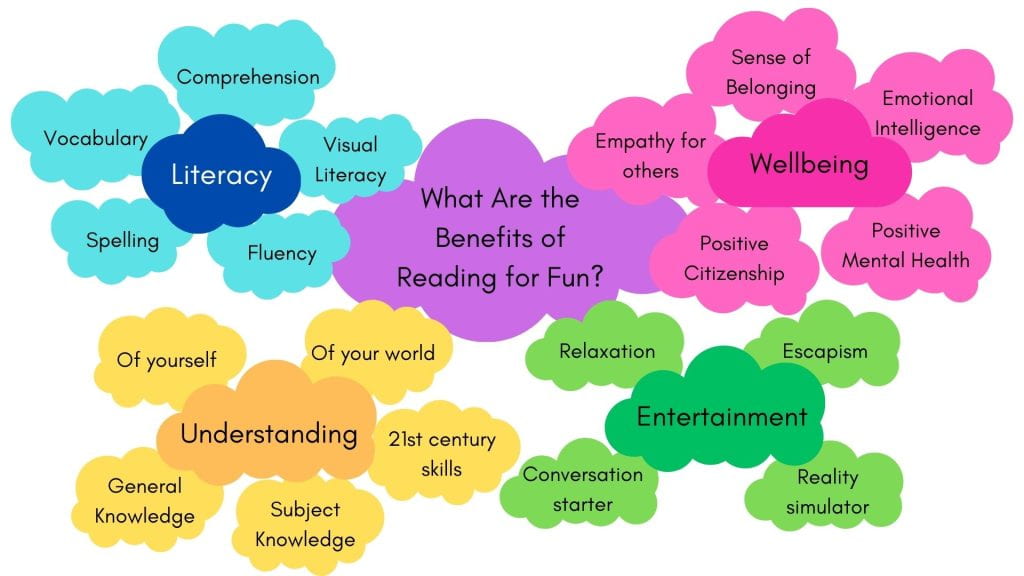

Developing a Whole-School Reading Culture

As I’ve discussed previously, some of my colleagues and I are in the early stages of planning a new whole-school reading culture initiative. We’ve made some small progress in this space over the last term and have begun putting together a strategic proposal (inspired by the work I completed during my degree) which we plan to eventually present to the Senior Executives at our school. One of the teachers has also taken the initiative to create a ‘Current Reads’ poster for the English staffroom windows which has already launched several conversations with students about reading for pleasure.

Action moving forward: Collaboratively develop the reading culture initiative proposal.

On my end, I’ve been working on developing a culture of pleasure reading in a number of different ways. This term I’ve been working on developing the Wide Reading Program for years 7 and 8, with all classes bar one participating. As always seems to be the case, these lessons experienced significant interruptions in Term 1, with 51% of lessons needing to be cancelled because of other programs using the library space, staff illness, public holidays, and other whole-school events. As a result, four of the ten participating classes have less than 50% program attendance, with two of those classes having had only one lesson to access the library and its resources.

To ameliorate the impacts of my absences when I was sick, I supported the classroom teachers in running the program themselves by providing the lesson materials. However, staff feedback suggests that the program runs best when I’m at the helm, reinforcing the value of a trained teacher-librarian’s expertise and skill in spreading a passion for reading!

Student feedback so far this term has also been positive. I’ve placed a significant emphasis on trying to build excitement around reading and on highlighting different reading behaviours in an attempt to get students to self-identify as readers. As such, we’ve played a variety of games such as Never Have I Ever and an adapted mad-libs game inspired by Cards Against Humanity which I’m calling Books Against Humanity. In this game students must obtain a variety of quotes from the book they’re reading and in small teams choose the best quote to complete the prompt I give them. There were a lot of laughs at this one, and it was great to see even reluctant readers engage with the task!

In large part due to the Wide Reading Program, our loans stats are strong so far this term. While this is not a hard and fast indication of reading culture, it does give some indication regarding the number of books ending up in student (and staff) hands. During Term 1 we loaned out 1140 resources from our physical and digital collections, surpassing the total loans for some previous years in their entirety. However, this is compared to the 1250 resources we loaned during the same time last year; the down-turn is due in part to falling student enrolments, the number of interruptions leading to the library’s closure, as well as a decrease in digital loans from our virtual library. Another pertinent fact emerging from this data is the increasing popularity of our magazines, with 31 loaned this term compared to only 2 in the same time last year.

Another way I’m trying to build a reading culture is by celebrating reading achievements in our school. I’m updating our Readerboard every month to show the students with the highest number of loans, and giving these students both merit certificates and house points in their roll calls to visibly highlight their achievement and show that we value reading. I’m also in the early stages of planning a celebratory afternoon for the students who finished the Premier’s Reading Challenge last year – they’ve chosen a movie afternoon as their reward, so hopefully other students will see their reward and want to get in on the action too! Another way I can increase participation is by embedding the challenge into the Wide Reading Program through read-alouds, book talks and activities such as the CBCA Shadow Judging.

Action moving forward: Embed PRC resources into the Wide Reading Program and continue developing activities to develop enthusiasm around reading.

Fostering Positive Wellbeing

Our school’s strategic plan has a strong focus on wellbeing; this is therefore an area where I can support the school community while advocating for the value of the library. I recently bought some of Margaret Merga’s books on this topic and intend to add them to our Teacher Reference collection, and can’t wait to read them to gain some more ideas on how to be active in this space.

So far this year, I’ve continued to support social-emotional learning through the provision of social clubs during the breaks. I’ve encouraged students to form their own clubs with my support, and as a result we’ve now added a Trading Card Game Day and Origami Club into our schedule, alongside our regular offerings of the Nintendo Switch Club and Dungeons and Dragons. While the Nerdvana Day didn’t get off the ground this term due to time constraints, this has previously been a great success with students and I will endeavour to make it a priority in Term 2. I have also discussed the possibility of a Year 12 Reading Retreat during their Trial exams to help them relax during this otherwise stressful period.

Action moving forward: Organise the Nerdvana Day and Year 12 Reading Retreat in Term 2.

These clubs and activities have had a significant impact on our daily visitor numbers, with an average 138 students visiting each break. Our biggest day was a whopping 334 students! While these increased visitor numbers contribute to a lot of noise and chaos in the library, they also represent an opportunity for students to be exposed to the reading culture I’m attempting to build, with several students who wouldn’t normally identify as readers borrowing books that they wouldn’t have come into contact with had they not been in the library space. However, the data suggests that our daily visitors and loans were trending down towards the end of term; this is no doubt due to the number of interruptions affecting the library’s ability to open in those later weeks, such as the fact that I’m not replaced when I’m absent. Ensuring continued access to the space is therefore an area for improvement in future.

Action moving forward: Advocate for the library space to be covered like any other playground duty in my absence.

Our Library Monitor program is also expanding, with several students approaching me throughout the term asking if they can join the program. Early in Term 2 I will incorporate these new students into the program and develop their skills as junior librarians in training. Their assistance is vital in helping maintain the library collections, especially as our loans increase.

Action moving forward: Train the incoming library monitors.

Maintaining Effective, Relevant Collections

Collection management is one of the biggest, most underappreciated aspects of our role as teacher-librarians, largely because so much of it is done behind the scenes and is therefore invisible to the majority of our school community. We’ve had an influx of student requests, so in addition to my plans to replace many of the outdated resources weeded over the last few years I’ve had to dedicate a significant portion of my budget to fulfilling these requests. As a result, there’s not a huge amount of money left for future purchases! A more balanced allocation of funds might be prudent in future years. However, one benefit of ordering so much so early in the year has been that we are getting a steady arrival of new resources to process in our systems as stock becomes available. This will hopefully allow us to spread out the accessioning process and reduce the number of orders we need to chase up at the end of the year.

Over the past few years I’ve invested a significant amount of time in updating our collection to ensure it’s relevant to the learning and recreational needs of our school community. When I first started, the fiction and non-fiction collections hadn’t been weeded for several years and the median date of publication was 1981. Last year our average date of publication was 2006, and I’m happy to report that due to my efforts last term this date is now 2010, while our median date is now 1995. While this is still not as up-to-date as I’d like, it’s a significant improvement.

I’m also in the process of cleaning up our catalogue and moving some items to locations where our students and staff are more likely to find them. I’ve set myself the goal of cleaning up 10 catalogue records a day, and while this isn’t always achievable it has made a significant impact on the number of resources with outdated or incorrect catalogue metadata.

Action moving forward: Complete catalogue clean-up.

Progressing with my Professional Development Plan

In NSW Department of Education schools, we are required to have a Professional Development Plan (PDP). This year I’ve set myself three somewhat ambitious goals.

Goal 1: To raise the perceived status, professionalism and value of the school library by ensuring its effective management. This will be achieved by conducting a needs assessment and creating a strategic plan aligned to the school’s Strategic Improvment Plan by the end of Term 3.

This is a huge goal with multiple steps, which is why I’ve set its completion at the end of Term 3. This term I asked for planning time and was knocked back, so have asked for time again in Term 2. I’ve submitted a proposal through my Head Teacher for this planning time to be during the HSC Trial exam period when the library would normally be closed; hopefully my line managers will see the value of this goal and understand my attempts to support the school while minimising disruption.

Action moving forward: Gain approval for planning time in week 9.

Goal 2: To support the diverse needs of our students by working with the Engaged Students for Learning committee to reintroduce a school-wide High Potential and Gifted (HPGE) education initiative.

This is another area where I’ve sadly made limited progress, largely due to the restrictive nature of our committee meeting schedule which has meant we’ve only had one official meeting last term. We were supposed to deliver a presentation during a staff meeting on how to identify and support HPG students, but beyond informal conversations with staff there’s been no movement in this space for me yet.

Action moving forward: Conduct an evaluation of existing HPGE activities with the committee.

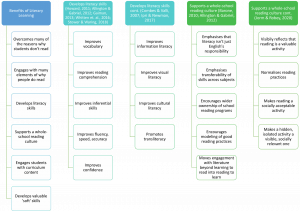

Goal 3: To forge strong connections between the library, teaching staff and students by supporting the implementation of the new English syllabus through the expansion of the Wide Reading Program and engagement with research into reading for pleasure and for information.

I feel that this is one area where I have successfully achieved my professional goal. The new English syllabus explicitly references reading for pleasure and our English faculty has embedded the Wide Reading Program into their units as a result of my continued advocacy over the past two years. I’ve also posted previously about my research into reading for pleasure, though more could be done in the information literacy space.

Action moving forward: Continue research into reading for pleasure and information; continue using data and feedback from students and staff to plan engaging activities which provide access and time for self-selected, socially supported reading with the Wide Reading Program.

Image 1: Reinsel Soulen, 2020, p.39

Image 1: Reinsel Soulen, 2020, p.39

Throughout ETL533 I have examined how I currently incorporate digital literature into our school and considered ways to increase this in future (

Throughout ETL533 I have examined how I currently incorporate digital literature into our school and considered ways to increase this in future (