Artificial Intelligence is an amazing, yet terrifying new technology that has the potential to be used for both good and evil in schools. As information specialists, Teacher-Librarians should be leaders in the space surrounding emerging technologies and how they can impact both teaching and learning – a difficult task considering that AI is evolving faster than a Pikachu with a Thunder Stone!

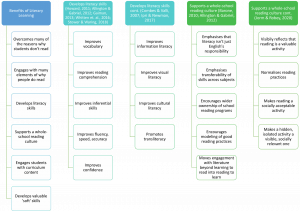

This year I’ve been doing a lot of research into reading for pleasure and investigating the best ways to build a reading culture in my school. As a result, I’ve got some pretty lengthy notes on the topic and it’s getting to the point where it’s all a bit overwhelming and I’m getting lost in the sheer amount of information I’ve gathered.

Enter ChatGPT. Despite it’s potential to cause harm in education, it also has great potential as a tool to maximise our efficiency. I decided to test out its capacity to summarise my notes so far and see whether it could help me make a bit more sense of the mountains of information I’ve gathered.

First Summary:

The research discusses various episodes related to overcoming barriers to reading for pleasure (RfP) as part of the Open University Reading for Pleasure (OURfP) initiative. Here are the key points summarized:

- Peer Role Models: Recognize the importance of peer role models in promoting reading for pleasure, especially if students lack role models at home.

- Different Reading Behaviors Count: Understand that all reading behaviors are valuable and that there’s a benefit in children seeing diverse reading role models beyond typical fiction lovers.

- Creating Communities of Readers: Shared experiences of reading the same books can create powerful communities of readers.

- Personalized Recommendations: Know the books students are reading, recommend similar books, relate to their reading experiences, and know the characters they love.

- Normalizing Reading Choices: Avoid denigrating students’ reading choices; share the idea of readers’ rights to validate all reading behaviors.

- Social Approach to Reading: Foster a culture of safety and non-judgmental reading choices through book talks, reading modeling, and promotion of different interests. Encourage student-led recommendations and involve parents in discussions and modeling.

- Factors Affecting Pleasure Reading: Understand the various barriers to pleasure reading, including lack of access to books, time, will, skills, and peer pressure. Address these barriers by increasing access to books, engaging in reading aloud activities, involving parents, and promoting authentic reading experiences.

- Synergies in Promoting Reading for Pleasure: These include constructing literate identities, intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy, text access, time and space, social interaction, and role modeling and connected communities.

Overall, the research emphasizes the importance of creating a supportive and inclusive reading environment, promoting diverse reading choices, and fostering positive reader identities among children and young people.

Second Summary

The ALIA Webinar: “Fostering a Passion for Reading” highlights strategies to promote reading culture and engagement, leveraging social media and community involvement. Key points include:

- Using Social Media: Social media platforms like Instagram can be powerful tools to connect with the community, promote reading, and engage learners. Schools can use existing popular templates but tailor them to focus on reading. Personal appearances and trending formats can enhance engagement.

- Collection Development: Understanding the community’s interests and needs is crucial for effective collection development. This involves community connection, consultation, and gap analysis to ensure a diverse and engaging collection. Weeding, sourcing from trusted suppliers, and regular acquisitions are essential steps in this process.

- Programming to Improve Reading Culture: Various programming, including reading lessons, book talks, read-alouds, and themed activities, can help foster a social reading culture. Offering a variety of activities, such as readers’ cups, staff book clubs, and themed weeks, can cater to diverse interests and preferences.

- Engaging Reluctant Readers: Strategies to engage reluctant readers include creating a supportive environment through social activities, targeted individual interviews to understand barriers to reading, and promoting a growth mindset towards reading. Programs like “Read with a Mate” aim to encourage social reading and provide personalized recommendations based on individual preferences.

Overall, the webinar emphasizes the importance of leveraging social media, understanding community needs, and implementing diverse programming to foster a passion for reading among students.

Third Summary

The series “Building a School Reading Culture” by Madison Dearnaley explores various aspects of cultivating a reading culture within educational institutions. Here are the key points from each part:

Part 1: Assessing Reading Culture

- Identifying a school’s reading culture involves observing factors such as library usage, collection layout, time allocated for reading, conversations about reading, and events like Book Week.

- Dr. Kay Oddone suggests strategically assessing and enacting organizational culture change to foster a reading culture.

Part 2: Understanding Organizational Culture

- Organizational culture influences how an institution operates and its members’ behavior.

- Developing a reading culture involves leadership, shared values, and aligning behavior with the desired culture.

Part 3: Strategies for Culture Change

- Culture change requires time and understanding behavioral drivers.

- A five-point strategy involves matching change strategies with existing culture, focusing on small behavioral shifts, honoring strengths, integrating formal and informal interventions, and measuring and monitoring progress.

Part 4: Defining Reading Culture

- A reading culture reflects how members of a school community value and engage with reading.

- It involves embedding reading across all aspects of school life and promoting reading for pleasure, intrinsic motivation, and autonomy.

- Strong leadership, a shared vision, and commitment to supporting the library are essential for building a reading culture.

Part 5: Measuring Reading Culture

- Measurement methods include surveys, data analysis, and review of strategic plans and policies.

- Key indicators of a strong reading culture include availability, opportunity, encouragement, intrinsic motivation, engagement, and choice.

Part 6: Identifying Reading Culture Characteristics

- Characteristics of a strong reading culture include providing opportunities for reading, promoting and supporting reading, fostering intrinsic motivation and engagement, and offering choice and autonomy.

- Measurement involves assessing resources, time allocation, visibility, staff involvement, reader motivation, engagement, and reader-driven collection development.

Part 7: Integrating Reading with School Values

- Integrating reading with school values such as creativity, global citizenship, entrepreneurship, and well-being can garner support for building a reading culture.

- Demonstrating the role of reading in achieving broader school goals can help prioritize reading initiatives and gain leadership support.

Each part emphasizes the importance of leadership, shared vision, community engagement, and strategic planning in cultivating a reading culture that supports student achievement and well-being.

Fourth Summary

The article “Getting Students Reading Through Social Media” by Overdrive, Nahomy Ortiz-Garcia, Melanie Wood, KC Boyd, and Amanda Hunt highlights effective strategies for using social media to engage students, staff, and parents in promoting reading. Here are the key points:

- Identify Audience and Encourage Interaction:

- Tailor content to engage with the audience by asking questions and encouraging interaction.

- Incorporate bite-sized content and involve students in posts to showcase their reading experiences.

- Celebrate Reading Milestones:

- Foster a culture of reading by celebrating reading achievements and milestones.

- Provide content with educational value and share additional reading resources and learning opportunities.

- Strategic Content Posting:

- Avoid overwhelming the audience by spacing out content and posting at optimal times when the audience is likely to be online and receptive.

- Content Ideas:

- Share school events, curriculum connections, holidays, student interests, and feature authors/illustrators.

- Make posts interactive and visually appealing to maintain engagement.

- Utilize Various Social Media Platforms:

- Use different social media platforms based on community engagement.

- Tell a unique story about your library reading program and keep posts concise.

- Promotional Strategies:

- Inform, define, and promote the reading program to parents, colleagues, and policymakers.

- Use memes, newsletters, usage tutorials, and QR codes/flyers at school events to promote library programs.

- Encourage Reading Through Curated Content:

- Create themed and curated book lists and understand feeder elementary school programming to tailor content accordingly.

- Engage in community programs and interactive scavenger hunts associated with prizes.

- Personal Connection and Visual Appeal:

- Show your face to build a connection with students, especially if you don’t see them daily.

- Use fun filters, visuals, and short videos to create exciting and relatable content.

- Consistent Content Creation:

- Set reminders for regular content creation and schedule it into your workday.

- Experiment with different social media platforms and content formats to find what works best for your audience.

- Useful Tools and Apps:

- Explore apps like CAPCUT for video editing and incorporate features like short video recommendations, trending book lists, author highlights, and new releases to keep the content fresh and engaging.

Implementing these strategies can effectively leverage social media to promote reading and foster a positive reading culture within the school community.

Overall Reflections on ChatGPT as a Research Summary Tool

As you can see, it’s done a fairly decent job of summarising the key points of my research. While ChatGPT does have great potential to save teachers time in this area, there are nonetheless a few limitations I’ve noticed:

- It can’t directly access or view specific webpages or documents. We therefore can’t simply enter a URL and tell it to summarise the key points of a webpage or pdf.

- It misidentified my notes as an article. There were other minor errors or parts where the AI failed to identify what I would have argued was the actual key point.

- It has a word limit for your input, which meant that I had to break my research up into chunks which resulted in the four separate summaries above.

- I tried to have it amalgamate these four separate summaries but it failed to synthesise the information effectively and instead created a bastardised, repetitive description rather than anything that would be of real use e.g. “Peer Role Models: Importance of peer influence in encouraging RfP.” I therefore didn’t post it here.

- The input function doesn’t appear to allow for easy formatting of paragraphs. It also didn’t reflect my bullet point hierarchy and therefore my notes were all lumped together.

- This is only a minor issue, but it took my Australian English spelling and spat it back out as US English e.g. ‘recognise’ became ‘recognize’. This hurt a little.

I was using the free ChatGPT version 3.5. Functionality is quite possibly improved in the upgraded GPT-4. For funsies, I also copied the summaries written by ChatGPT and asked it whether it wrote it to see whether it would potentially pick up on any plagiarism; it correctly identified this content as generated by ChatGPT: “‘Yes, I wrote the summaries you provided in your earlier message.” I’m not sure how effective it would be at picking up content generated by other AI tools, however; this might be an experiment for another day.

Overall, while it certainly saved time summarising my research, this would not be an effective way to create summary notes without having first done the initial note-taking process. We therefore need to caution our students not to rely solely on AI but to still use the old noggin to create their notes first, and always read through to fact check any content generated by these wondrous, alarming, and soon to be ubiqituous tech gremlins.

Throughout ETL533 I have examined how I currently incorporate digital literature into our school and considered ways to increase this in future (

Throughout ETL533 I have examined how I currently incorporate digital literature into our school and considered ways to increase this in future (