In the light of your readings and your experience of different digital literatures write a critical reflection which considers the following issues:

• What makes a good digital text, what counts as one, and what purpose do digital texts serve?

• Compare your experience of reading digital texts with reading print.

• Choose the digital text you most enjoyed and discuss how you might incorporate it into a program at your institution.

As my research into digital literature has progressed, my understandings have simultaneously narrowed and blurred regarding this nebulous topic. I have encountered numerous definitions, categories, and subcategories in my research, including the commonly repeated broad distinction between the digital and the digitised (Strickland, n.d., para. 3; Hayles, 2007, para.10; Bourchardon & Heckman, 2012, p.1; Heckman & O’Sullivan, 2018, para.4).

Many attempts to define digital literature have focused on what it is not. For instance, electronic literature is not something that can be printed (Strickland, n.d., para.3; Sargeant, 2015, p.455; Wright, 2019, para.2), thereby excluding e-books which digitise existing print texts (Writerful Books, n.d., para.10) as ‘paper-under-glass’ texts (Allan, 2017, p.22) which, while popular with publishers, do not take advantage of many potential features offered by emerging digital platforms (McGeehan et al., 2018, p.62-63). However, excluding these texts from discussions about digital literature arguably ignores their popularity and potential as learning and engagement tools, especially in schools; after all, this unit is called ‘Literature in Digital Environments’ and not ‘Digital Literature’ for a reason, and it would be unwise to eliminate digitised texts from discussion altogether. I personally prefer to read digitised e-books due to the ability to increase font size and define unknown words, yet my favoured features were missing from many of the digital texts I’ve explored so far (Lysaught, 2022a).

Other definitions focus on common features of digital texts, such as their exploitation of digital characteristics (Bourchardon & Heckman, 2012, p.1), their inherent multimodality (Walker et al., 2010, p.219; Mills & Levido, 2011, p.80; Heckman & O’Sullivan, 2018, para.11) or the way they use interactivity and connectivity to position the audience in the process of either constructing meaning or constructing the text itself (Serafini, 2013, p.403; Walsh, 2013, p.181; Bell, 2016, p.295-296; Wall, 2016, p.35; Allan, 2017, p.23-24). These multidimensional features allow readers a different experience to that of reading a traditional unidimensional printed text, with some research suggesting that changes to reading speed and navigation in digital environments can affect comprehension and memory (Jabr, 2013, para.10, 20). Lending data and anecdotal discussions in my school suggest printed texts have maintained their top position as preferred reading materials amongst both staff and students, though this may have more to do with digital poverty, lack of exposure and competing distractions on devices than the potential offered by digital texts.

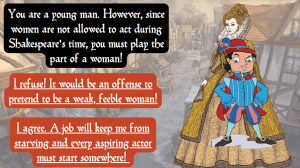

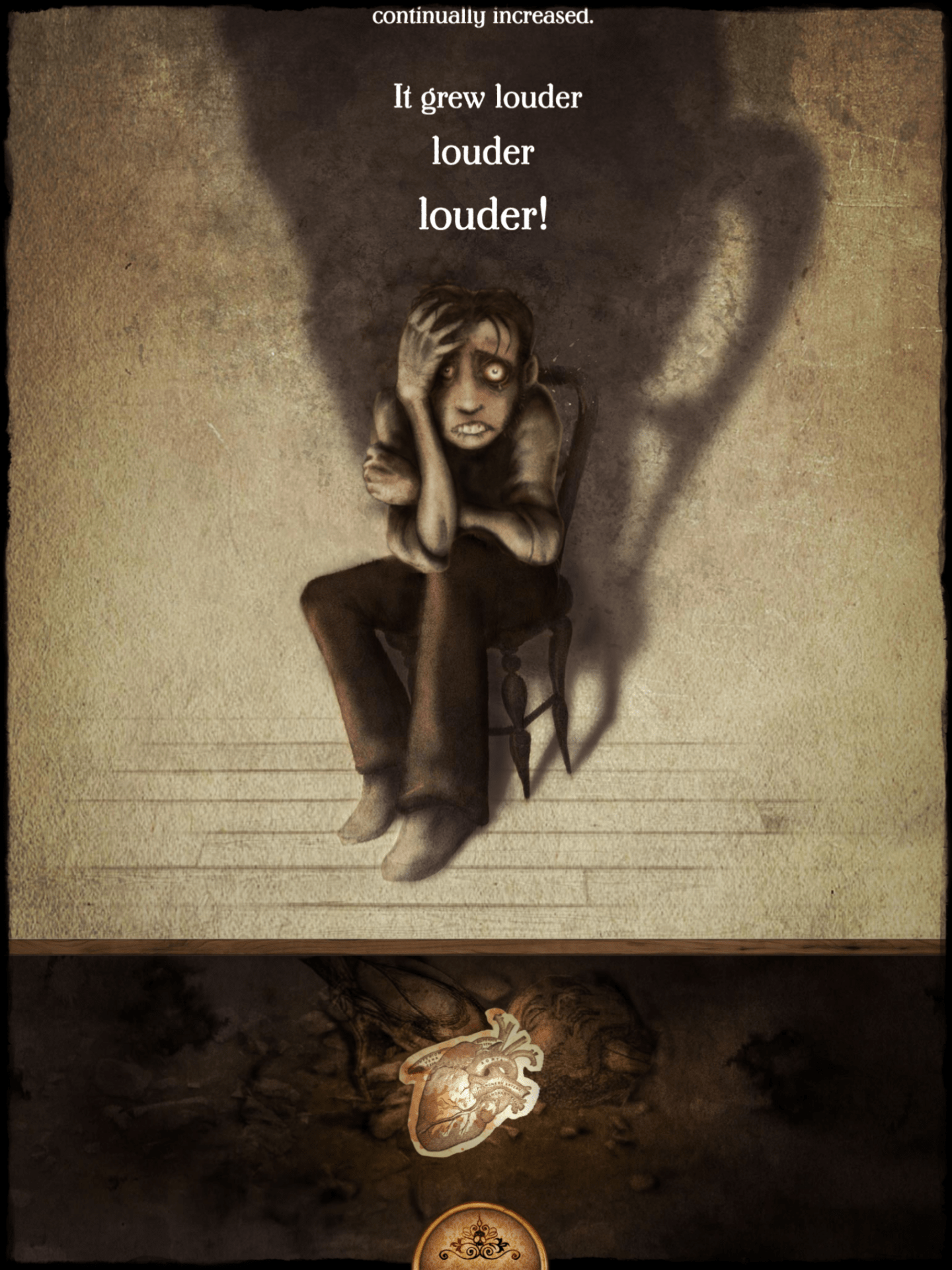

Another useful categorical framework I used to structured my reviews resulted from my early combination (Lysaught, 2022b, para.2-3) of Allan (2017, p.22-23) and Unsworth’s (2006, p.2-3) distinctions between recontextualised or digitised literary texts, enhanced app or electronically augmented texts, and ‘born digital’ texts. However, my increased exposure to digital literature revealed that often digital narratives defy simplistics attempts at categorisation, with all three reviewed texts blurring boundaries depending on whose definition one applied (Lysaught, 2022c, 2022d, 2022e).

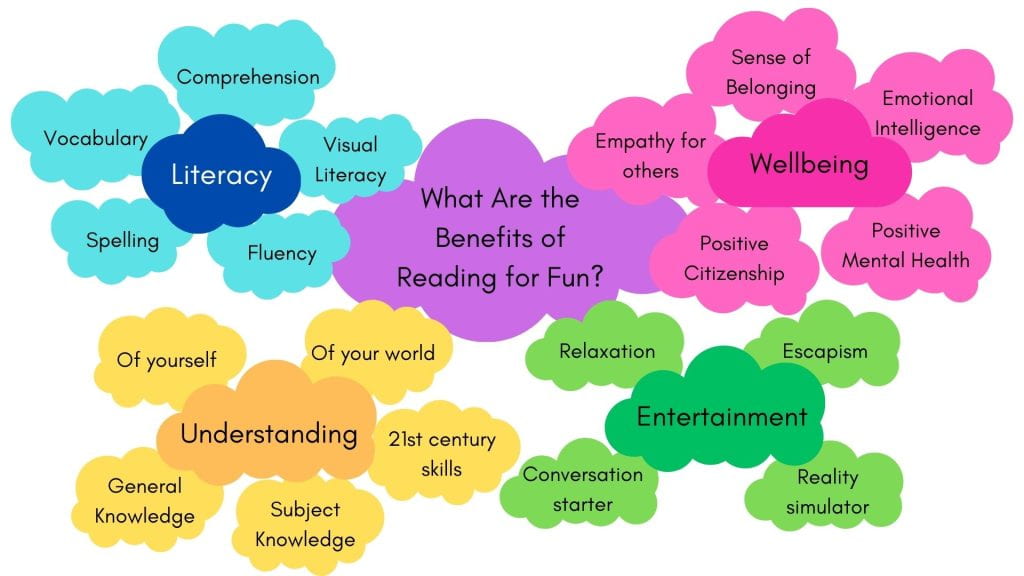

Inspired by my reviewed texts, I decided to play with the multimodal potential offered by this blog to create a word-cloud of my notes so far. Several key ideas emerge, including: a focus on the relationship between readers, authors, teachers and the act of reading; the relationship between technology and meaning-making processes; and new literacies focused on mixed media and formats such as digital devices and internet platforms.

As a result of this research, I conclude that quality digital literature involves the interplay of three core elements: multimodality, interactivity, and connectivity (whether to the world or content of the text and/or to other users and platforms). Early attempts to construct an evaluative criteria (Lysaught, 2022f) have solidified into the criteria below:

😍 = yes, love it!

🤔 = hmm … somewhat?

👎 = not really/not evident

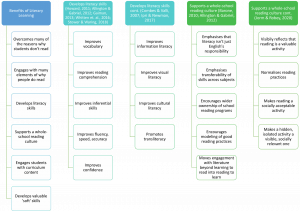

Arguably, defining digital literature is less important in school contexts than how it can be used to support the needs, interests and abilities of the school community. I discussed in each review how these texts could effectively support teaching and learning in my school community (Lysaught, 2022c, 2022d, 2022e). Early in my journey I posited that teacher-librarians could be invaluable in aligning new pedagogies with innovative digital narratives to support time-poor staff (Lysaught, 2022g, 2022b). Anecdotal evidence suggests that digital literature is a powerful tool for engaging students as readers (Lysaught, 2022h). Moving forward, I am interested in harnessing digital literature and its associated social networking to motivate reluctant students (Lysaught, 2022a) as part of my Year 7 Wide Reading Program.

747 words.

Reference list:

Allan, C. (2017). Digital fiction: ‘Unruly object’ or literary artefact? English in Australia, 52(2), 21-27.

Bell, A. (2016). Interactional metalepsis and unnatural narratology. Narrative, 24(3), 294-310.

Bourchardon, S., & Heckman, D. (2012). Digital manipulability and digital literature. Electronic Book Review.

Hayles, K. (2007). Electronic literature: What is it? https://www.eliterature.org/pad/elp.html

Heckman, D., O’Sullivan, J. (2018). Electronic literature: contexts and poetics. Literary Studies in the Digital Age: An Evolving Anthology.

Jabr, F. (2013, April 11). The reading brain in the digital age: The science of paper versus screens. Scientific American.

Lysaught, D. (2022a, August 13). ETL533 3.2 Exploring digital forms. All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/08/13/etl533-3-2-exploring-digital-forms/

Lysaught, D. (2022b, August 7). ETL533 2.3: Challenges of using digital literature in the classroom. All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/08/07/etl533-2-3-challenges-of-using-digital-literature-in-the-classroom/

Lysaught, D. (2022c, August 28). ETL533 Assessment 2 Part A: Review 1 – Over the Top by The Canadian War Museum (n.d.). All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/08/28/etl533-assessment-2-part-a-review-1-over-the-top-by-the-canadian-war-museum-n-d/

Lysaught, D. (2022d, August 28). ETL533 Assessment 2 Part A: Review 2 – iPoe by iClassics Collection (2012-2015). All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/08/28/etl533-assessment-2-part-a-review-2-ipoe-by-iclassics-collection-2012-2015/

Lysaught, D. (2022e, August 28). ETL533 Assessment 2 Part A: Review 3 – Dracula Daily by Matt Kirkland (2021). All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/08/28/etl533-assessment-2-part-a-review-3-dracula-daily-by-matt-kirkland-2021/

Lysaught, D. (2022f, August 14). ETL533 Evaluating digital literature: Deeper considerations. All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/08/14/etl533-evaluating-digital-literature-deeper-considerations/

Lysaught, D. (2022g, July 19). ETL533 Evaluating digitally reproduced stories. All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/07/19/etl533-1-2-evaluating-digitally-reproduced-stories/

Lysaught, D. (2022h, July 25). ETL533 Assessment 1: Online reflective journal blog task. All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/07/25/etl533-assessment-1-online-reflective-journal-blog-task/

McGeehan, C., Chambers, S., & Nowakowski, J. (2018). Just because it’s digital, doesn’t mean it’s good: Evaluating digital picture books. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 34(2), 58-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2017.1399488

Mills, K.A., & Levido, A. (2011). iPed: pedagogy for digital text production. The Reading Teacher, 65(1), 80-91.

Sargeant, B. (2015). What is an ebook? What is a book app? And why should we care? An analysis of contemporary digital picture books. Children’s Literature in Education, 46(4), 454-466.

Serafini, F., Kachorsky, D. & Aguilera, E. (2015). Picture books 2.0: Transmedial features across narrative platforms. Journal of Children’s Literature, 41(2), 16-24.

Strickland, S. (n.d.). Born digital. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69224/born-digital

Unsworth, L. (2006). E-literature for children: Enhancing digital literacy learning. Routledge.

Walker, S., Jameson, J., & Ryan, M. (2010). Skills and strategies for e-learning in a participatory culture (Ch. 15). In R. Sharpe, H. Beetham, & S. Freitas (Eds.), Rethinking learning for a digital age: How learners are shaping their own experiences (pp. 212-224). New York, NY: Routledge

Wall, J. (2016). Children’s literature in the digital world: how does multimodality support affective, aesthetic and critical response to narrative? by Alyson Simpson and Maureen Walsh. An extended abstract by June Wall. SCAN 35(3), 34-36.

Walsh, M. (2013). Literature in a digital environment (Ch. 13). In L. McDonald (Ed.), A literature companion for teachers. Marrickville, NSW: Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA).

Wright, D. T. H. (2019, July 10). From Twitterbots to VR: 10 of the best examples of digital literature. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/from-twitterbots-to-vr-10-of-the-best-examples-of-digital-literature-110099

Writerful Books (n.d.). New $10,000 digital literature award. https://writerfulbooks.com/digital-literature-award/

Throughout ETL533 I have examined how I currently incorporate digital literature into our school and considered ways to increase this in future (

Throughout ETL533 I have examined how I currently incorporate digital literature into our school and considered ways to increase this in future (