How can we take the perception of the TL’s role from the keeper and stamper of books in the quiet place to something different?

I think it’s fair to say that as a profession teacher-librarians have an image problem. Way back at the start of this degree I wrote about Bonanno’s keynote speech in which she described teacher-librarians as an ‘invisible profession’ (Lysaught, August 29 2021a) and the misconception that the library is purely about books (Lysaught, August 29 2021b). A 2021 study revealed that in the US, teacher-librarian numbers declined 20% in the past decade (Ingram, July 19, 2021), and this trend of shrinking school libraries is being replicated in Australia (Tidball, February 10, 2023) alongside stagnating or declining budgets, staffing levels, and staff engagement or support (Softlink, 2022, p.6-7).

Maybe, like a good dancer, we make our work look effortless. Maybe too much of what we do is in the background of busy teachers’ days. One thing that’s for sure is that we need to work on improving our visibility and perceived value to our school community if we are to ensure the future of our profession (Weisburg, 2020).

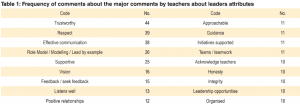

Moir, Hattie and Jansen (2014, p.37) identified a number of key attributes that teachers perceived as important for leaders:

They also state that “Trust is often best developed in team environments, as then there is opportunity for collaboration and shared decision-making, especially when there is a common focus on improving teaching and learning” (p.39). Bush and Glover (2014, p.554) also discuss the idea of leadership as influence rather than stemming from formal authority, which suits teacher-librarians since we often lack official leadership positions in school hierarchies. Both discussions relate beautifully to the work of the teacher-librarian as literacy expert and information specialist, and they highlight a key way that teacher-librarians can both improve their visibility and their perceived value to their school community through collaborative programming, teaching, and assessment which supports the work of time-poor classroom teachers.

The work of Crippen and Willows (2019, p.174) highlights the 10 characteristics of servant-leaders, and teacher-librarians are uniquely placed to assist healing for colleagues overburdened by heavy workloads, administrivia, and poor student behaviour: “Through their actions as servant leaders they are facilitating a healing process and followers often look to them for support when times are difficult or something traumatic has occurred (Barbuto and Wheeler, 2007).” Teacher-librarians can also exhibit the persuasion trait of servant-leaders: “Supovitz (2018) also describes how teacher leaders use strategies such as leading by example, earning their colleagues trust and encouraging and collaborating with their peers.”

Another area where teacher-librarians can shift the perception of the school community is in the space surrounding emerging or rapidly changing technologies. A 2016 article notes that “By virtue of their training, relationships, systems knowledge, and instructional roles … teacher librarians are ideally suited to lead, teach, and support students and teachers in 21st century schools” (Digital Promise, 2016). Digital literature has the potential to move students from passive consumers to active creators of content while engaging them with the process and ethics of digital content creation (Lysaught, October 4 2022), and Artificial Intelligence is another emerging space where teacher-librarians can position themselves as experts to increase their visibility and perceived value (Lysaught, March 5 2023). It is imperative that we stay current with new and developing technologies to best position ourselves as experts in this field. Our expertise in copyright and the ethics of digital tools alongside our ability to connect the General Capabilities to specific learning programs is invaluable – however, we need to ensure that we’re promoting our abilities in this area and marketing collaborative teaching and planning as a benefit to time-poor teachers rather than just another thing to add to their plates.

Weisburg (2020) argues that while there are numerous barriers to showcasing our value, as a profession we have no other option. We must make it a priority to develop our visibility and promote our value to our school community or we run the risk of becoming obsolete. Weisburg suggests that teacher-librarians should start by looking for ways to showcase what we’re already doing; social media posts, visible displays, and staff emails can promote this work among the school community, while annual library reports can increase the perception of our professionalism and showcase for senior leaders much of the behind the scenes work that goes into running a library (Lysaught, March 5 2023). Weisburg’s suggestion about speaking at P&C meetings is another interesting one which links well to our aforementioned technology expertise. The most crucial aspect of Weisburg’s article for me was the concept of “chopportunities” – “challenges that can be turned into an opportunity.” So much of what affects the library is decided without our input and while it can be tempting to fall into the “why bother?” disheartened state of mind, for our own protection (and sanity!) reframing these issues as “chopportunities” can be a way to reclaim some sense of agency and showcase the benefits we provide to our school communities.

References:

Bush, T. & Glover, D. (2014). School leadership models: What do we know? School Leadership and Management, 34(5), 553-571. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2014.928680

Crippen, C. & Willows, J. (2019). Connecting teacher leadership and servant leadership: A synergistic partnership. Journal of Leadership Education, 18(2), pp. 171-180. https://journalofleadershiped.org/jole_articles/connecting-teacher-leadership-and-servant-leadership-a-synergistic-partnership/

Digital Promise (2016). The new librarian: Leaders in the digital age. In SCIS Connections, (96). https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-96/the-new-librarian-leaders-in-the-digital-age/

Moir, S., Hattie, J. & Jansen, C. (2014). Teacher perspectives of ‘effective’ leadership in schools. Australian Educational Leader, 36(4), 36-40.

Softlink (2022). 2022 Australian and New Zealand school library survey report. https://www.softlinkint.com/resources/reports-and-whitepapers/

Weisburg, H. K. (2020). Leadership: There is no other option. Synergy, 18(1). https://slav.vic.edu.au/index.php/Synergy/article/view/369/364

Watch Video

Watch Video