ETL402 has greatly expanded my understanding of how children’s literature is more than a literacy tool only useful in the English classroom. This unit has built on the knowledge I’ve developed over the last 10 years as an English/History teacher and expanded my understanding of new literacies and text types that have evolved (largely due to new technologies) since I finished my Master of Teaching in 2011.

Literary learning – teaching curriculum content through literature – is a powerful tool to develop students’ multiliteracies. In a changing information landscape, it is crucial that we develop multiliterate students who are flexible, have the skills to reformulate knowledge and practice, and can make meaning via multiple modes and formats (Anstey & Bull, 2006, p.19-21; Gorgon & Marcus, 2013, p.42). Sometimes as classroom teachers we can get stuck in a rut and it’s hard to find the time to explore new developments. ETL402 exposed me to new, exciting text types such as digital narratives (Lysaught, 2022a, para.4-6) and emphasised that teacher-librarians, acting as a mediators for time-poor classroom teachers, should seek out, explore, and curate useful resources to ensure that our colleagues have the best tools possible to teach our students (Braun, 2010, p.47; Lysaught, 2022b, para.6).

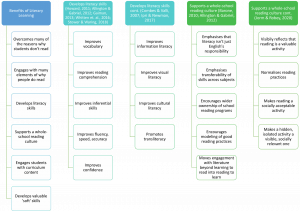

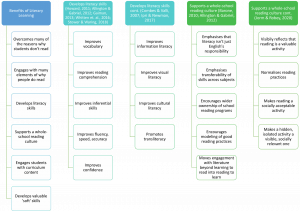

While many ETL401 readings emphasised that libraries were about more than just books (Lysaught, 2021a, para.8-9; Lysaught, 2021b, para.7-8, 15), ETL402 reminded me about reading’s importance and the value of literature across the curriculum (Lysaught, 2021c, para.1, 5). Like my peers (Poyitt, 2021, para.1), it troubles me that so many teens I work with simply don’t read. ETL402 made me question my own practices, preferences, and habits (Lysaught, 2021e, para.1-2). Many readings and discussions explored the reasons why people read or don’t, leading me to create these infographics:

These readings gave me valuable insights and inspiring strategies to inform my future practice as I work towards building a whole-school reading culture (Fulton, 2021, para.1; Shaw, 2021, para.2-9; Lysaught, 2022b, para.5; Lysaught, 2022c, para.2-3; Lysaught, 2022d, para.4-6). Literary learning is a particularly exciting way to build whole-school reading culture which I plan to implement to benefit my school community, as summarised in my infographics which I plan to share with my colleagues:

Moving forward, I understand that as information specialist, curriculum leader, and literacy expert, I should:

- Offer professional development opportunities for staff wishing to engage their students with literary learning;

- Collaboratively plan for the implementation of literary learning with classroom teachers;

- Implement literary response strategies with my own classes and support colleagues’ implementation e.g. Book Bento Boxes, Literature Circles;

- Curate appropriate resources to support staff and student needs and interests;

- Encourage further investigation and continued pleasure reading with a diverse, relevant, accessible collection;

- Effectively display and promote relevant materials as well as successful literary learning units via parent bulletins, social media, staff meetings, and school reports;

- Work with other stakeholders (e.g. Head Teacher Teaching and Learning, Literacy Committee Co-ordinator) to collect and analyse data determining the efficacy of literary learning;

- Draw upon the expertise and strengths of numerous staff to build a more effective whole-school reading culture which supports students’ personal and academic needs;

- Be responsive to the changing information landscape, time-pressures, and other issues (e.g. Covid restrictions) which may hinder implementation of collaborative practice

Bibliography:

Allington, R. L., & Gabriel, R. E. (2012). Every child every day. Educational Leadership, 69(6), 10-15.

Anstey, M., & Bull, G. (2006). Chapter 2: Defining multiliteracies. In M. Anstey & G. Bull (Eds.) Teaching and learning multiliteracies: Changing times, changing literacies. International Reading Association.

Barone, D. M. (2010). Children’s literature in the classroom: Engaging lifelong readers. Guildford Publications.

Braun, P. (2010). Taking the time to read aloud. Science Scope, 34(2), 45-49.

Brugar, K. A., & McMahon Whitlock, A. (2019). “I like […] different time periods:” elementary teachers’ uses of historical fiction. Social Studies Research and Practice 14(1), 78-97.

Carrillo, S. (2013, June 14). The power of a single story. Facing History & Ourselves. https://lanetwork.facinghistory.org/the-power-of-a-single-story/

Combes, B., & Valli, R. (2007). Fiction and the twenty-first century: A new paradigm? Paper submitted to Cyberspace, D-world, e-learning. Giving schools and libraries the cutting edge, 2007 IASL Conference, Taipei, Taiwan.

Daley, P. (2014, November 6). Anzac and Gallipoli are the novelist’s terrain as much as the historians. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/australia-books-blog/2014/nov/06/-sp-anzac-gallipolli-novelists-terrain-as-much-as-historians

Dickenson, D. (2014). Children and reading: literature review. University of Western Sydney, Australian Government, and Australia Council for the Arts.

Donnelly, D. (2017). Multi-platformed historical fiction: Literacy, engagement and historical understanding. SCAN 36(3), 43-47.

Earp, J. (2015, March 3). The power of a good book. Teacher. https://www.teachermagazine.com/au_en/articles/the-power-of-a-good-book

Fulton, A. (2021, November 17). Re: 1.2: Affirmative action – examples of practice [Online discussion comment]. Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_58477_1&conf_id=_115076_1&forum_id=_259135_1&message_id=_3855912_1&nav=discussion_board_entry

Gaiman, N. (2013, October 16). Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming

Gorgon, B. & Marcus, A. (2013). Lost in transliteracy: How to expand student learning across a variety of platforms. Knowledge Quest, 41(5), 40-45.

Howard, V. (2011) the importance of pleasure reading in the lives of young teens: Self-identification, self-construction and self-awareness. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 43(1), 46-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000610390992

Ipri, T., & Newman, B. (2017). Beginner’s guide to transliteracy: Where did the term transliteracy come from? Libraries and Transliteracy. https://librariesandtransliteracy.wordpress.com/beginners-guide-to-transliteracy/

Jorm, M. & Robey, L. (2020, December 7). Libraries as literacy leaders. National Education Summit. https://nationaleducationsummit.com.au/new-blog/librariesasliteracyleaders

Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science 342(6156), 377-380.

Krashen, S. D. (2011). Free voluntary reading. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Lysaught, D. (2021a, July 19) ETL401 assessment 1: What is the role of the teacher librarian? All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/07/19/etl401assessment1/

Lysaught, D. (2021b, August 29) ETL401 3.2 the role of the teacher librarian: LIBERating our perceptions. All You Read Is Love.

https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/08/29/3-2-the-role-of-the-teacher-librarian-liberating-our-perceptions/

Lysaught, D. (2021c, July 19) ETL402 half-session reflections: The function of historical fiction in secondary schools. All You Read Is Love.

https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/category/etl402/

Lysaught, D. (2021d, December 26) ETL402 3.1 strategies to leverage a love of reading. All You Read Is Love.

https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/12/26/etl402-3-1-strategies-to-leverage-a-love-of-reading/

Lysaught, D. (2021e, December 31) Top reads 2021. All You Read Is Love.

https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/12/31/top-reads-2021/

Lysaught, D. (2022a, January 3) ETL402 5.1 practical idea and digital text to support literary learning. All You Read Is Love.

https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/01/03/etl402-5-1-practical-idea-and-digital-text-to-support-literary-learning/

Lysaught, D. (2022b, January 10) ETL402 6.1-2 teaching and promotion strategies for using literature. All You Read Is Love.

https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/01/10/etl402-6-1-2-teaching-and-promotion-strategies-for-using-literature/

Lysaught, D. (2022c, January 17) ETL402 6.3 responding to literature: The read aloud. All You Read Is Love.

https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/01/17/etl402-6-3-responding-to-literature-the-read-aloud/

Lysaught, D. (2022d, January 17) ETL402 6.2 curriculum-based literary learning: Year 9 English power and freedom. All You Read Is Love.

https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/01/17/etl402-6-2-curriculum-based-literary-learning-power-and-freedom/

Manuel, J., & Carter, D. (2015). Current and historical perspectives on australian teenagers’ reading practices and preferences. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy 38(2), 115-128.

Poyitt, B. (2021, November 29). Re: 1.2: Affirmative action – examples of practice [Online discussion comment]. Interact 2.

https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_58477_1&conf_id=_115076_1&forum_id=_259135_1&message_id=_3855912_1&nav=discussion_board_entry

Rodwell, G. (2019). Using fiction to develop higher-order historical understanding. In T. Allender, A. Clark & R. Parkes (Eds.), Historical thinking for history teachers: A new approach to engaging students and developing historical consciousness (p.194-207). Allen & Unwin.

Shaw, B. (2021, December 22). Re: 3.1: Strategy to leverage a love of reading [Online discussion comment]. Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_58477_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_115076_1&forum_id=_259138_1&message_id=_3855937_1

Smith, A. K. (2019, October 14). Literature has the power to change the world. Here’s how. Books At Work. https://www.booksatwork.org/literature-has-the-power-to-change-the-world-heres-how/

Stower, H. & Waring, P. (2018, July 16). Read like a girl: Establishing a vibrant community of passionate readers. Alliance of Girls Schools Australia. https://www.agsa.org.au/news/read-like-a-girl-establishing-a-vibrant-community-of-passionate-readers/

Taylor, T., and Young, C. (2003). Making history: a guide for the teaching and learning of history in Australian schools. Curriculum Corporation.

Wadham, R. L., Garrett, A. P., Garrett, E. N. (2019). Historical fiction picture books: the tensions between genre and format. The Journal of Culture and Values in Education 2(2), 57-72.

Whitten, C., Labby, S., & Sullivan, S. L. (2016). The impact of pleasure reading on academic success. The Journal of Multidisciplinary Graduate Research 2(4), 48-64.

Wu, Y., Mallan, K., & McGillis, R. (2013). Reimagining the world: Children’s literature’s responses to changing times. Springer.

Young, S. (2012). Understanding history through the visual. Language Arts 89(6), 379-395.

The infographics in this post are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The infographics in this post are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.