My understanding of digital literature has grown significantly over the last few months. From my early definitions to the creation of my own narrative, I’ve gained a solid understanding of what digital literature is, why it’s beneficial and how it can be implemented to support my school.

My preliminary definitions of digital literature focused on the distinction between the digital and the digitised (Lysaught, 2022, July 19; Lysaught, 2022, July 25). As my research progressed I consolidated these distinctions by combining Unsworth’s (2006, p.2-3) and Allan’s (2017, p.22-23) categories (Lysaught, 2022, August 7). Like my peers (Curtis, 2022, July 19), I believe digital literature should be quality and meet community needs, which led me to consider what makes quality digital literature (Lysaught, 2022, August 14) and to design my own evaluation criteria where I determined three key aspects: multimodality, interactivity, and connectivity (Lysaught, 2022, August 28). Self-evaluations and peer feedback reveals – despite the amateur multimodal features – mine’s an effective, quality text suitable for its intended purpose and audience:

However, defining digital literature is arguably less important to teacher-librarians than understanding how to incorporate it effectively. Digital literature provides exciting opportunities to move students from passive consumers to active creators of content (Morra, 2013, para.2; Kitson, 2017, p.66), and as new technologies and communication tools emerge, students require new literacies to ensure they’re critically consuming and ethically creating texts (Walker et al., 2010, p.214-216; Kearney, 2011, p.169; Leu, 2011, p.6-8; Mills & Levido, 2011, p.80-81, 89; Leu et al., 2015, p.139-140; Serafini et al., 2015, p.23; Combes, 2016, p.4). In 2009 students spent an average four hours a day online (Weigel, 2009, p.38); by 2015 US teens consumed between 6-9 hours of media a day (Common Sense Media, 2015, para.6), while Australian teens now spend an average of 14.4 hours a week online (eSafety Commissioner, 2021, p.4). Digital literature therefore harnesses our students’ preferences and familiarity with technological platforms (Figueiredo & Bidarra, 2015, p.323; Skaines, 2010, p.100-104; Stepanic, 2022, p.2; Weigel, 2009, P.38). Digital literature incorporating interactivity, multimodality, and connectivity can develop ‘nöogenic narratives’ wherein personal growth is achieved by viewing our lives as a story (Hall, 2012, p.97), a key element of the English syllabus (NSW Standards Authority, 2019, p.10). Research shows that educators can exploit digital narratives to create meaningful and authentic learning opportunities for students to create personal and academic growth (Bjørgen, 2010, p.171-172; Dockter et al., 2010, p.419; Hall, 2012, p.99; Reid, 2013, p.38-41; Smeda et al., 2014, p.19; Sukovic, 2014, p.222-226).

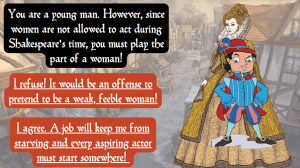

However, educators must carefully consider the purpose of integrating digital narratives into their programmes. While research reveals digital texts’ benefits supporting young, emerging, or struggling readers and developing transliteracy (Tackvic, 2012, p.428; Cahill & McGill-Franzen, 2013, p.32-33; Matthews, 2014, p.29; McGeehan et al., 2018, p.58), others raise issues regarding reading comprehension, retention, and attention (Cull, 2011, para.35-38; Goodwin, 2013, p.79; Jabr, 2013, p.5-30; McGuire, 2015, para.30-35). Technology should be used as a meaningful tool, not just as a gimmick. Monsen (2016) explored the idea that we are “quintessentially cyborgs” due to the symbiotic relationship between humanity and technology. My research into digital learning frameworks such as the SAMR model (Lysaught, 2022, August 6) revealed that effective implementation of technology should not replace, but co-exist with and supplement existing print literacies. Printed choose-your-own-adventure narratives arguably improve literacy (Chooseco & Hofmann, 2016, para. 8-9) and can be updated using digital features to form powerful digital texts (Farber, 2015, para.1-2). Thus, my own digital narrative was designed as an immersive, interactive, multimodal resource to develop students’ understanding of life in Shakespearean England while supplementing traditional print resources and online information sources.

Throughout ETL533 I have examined how I currently incorporate digital literature into our school and considered ways to increase this in future (Lysaught, 2022, July 31; Lysaught, 2022, August 7; Lysaught, 2022, August 13). As discussed with my peers (Macey, 2022, September 24; Barnett, 2022, September 27; Facey, 2022, September 29) difficulties arise surrounding cost-effectiveness, storage, access, and user preferences that often impede digital literature’s success in schools. Despite these challenges, after creating my own digital narrative I strongly believe that student-created digital texts can enhance their own learning and connections to content, and integrate well with Guided Inquiry units and literary learning (Lysaught, 2022, January 27; Lysaught, 2022, August 14; Lysaught, 2022, September 3; Lysaught, 2022, September 16). Peer feedback also supports this (Lysaught, 2022, September 3). Due to this unit I am more aware of my students’ discussions around digital literature (Lysaught, 2022, July 25; Lysaught, 2022, August 28), revealing these are powerful texts with which students are already engaging. Literature in digital environments allows teacher-librarians to show our value to our school community, as we can support time-poor staff as they include more captivating, rich resources and utilise digital narratives to support our students with various interests and literacy needs.

Throughout ETL533 I have examined how I currently incorporate digital literature into our school and considered ways to increase this in future (Lysaught, 2022, July 31; Lysaught, 2022, August 7; Lysaught, 2022, August 13). As discussed with my peers (Macey, 2022, September 24; Barnett, 2022, September 27; Facey, 2022, September 29) difficulties arise surrounding cost-effectiveness, storage, access, and user preferences that often impede digital literature’s success in schools. Despite these challenges, after creating my own digital narrative I strongly believe that student-created digital texts can enhance their own learning and connections to content, and integrate well with Guided Inquiry units and literary learning (Lysaught, 2022, January 27; Lysaught, 2022, August 14; Lysaught, 2022, September 3; Lysaught, 2022, September 16). Peer feedback also supports this (Lysaught, 2022, September 3). Due to this unit I am more aware of my students’ discussions around digital literature (Lysaught, 2022, July 25; Lysaught, 2022, August 28), revealing these are powerful texts with which students are already engaging. Literature in digital environments allows teacher-librarians to show our value to our school community, as we can support time-poor staff as they include more captivating, rich resources and utilise digital narratives to support our students with various interests and literacy needs.

Word count: 806

Reference list: https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/10/04/etl533-assessment-4-reference-list/