Part A: Statement of Personal Philosophy

Effective 21st century teacher-librarians require strong interpersonal skills alongside the pedagogical knowledge to teach a multitude of competencies and literacies across different curriculum areas. Through proficient leadership, strategic planning, resource management, and innovative program design, modern teacher-librarians inspire passion for reading for pleasure and information while supporting learning and wellbeing in our communities.

Modern libraries are about people, not just resources. Our ability to form effective relationships with students, staff, parents, and professional networks allows teacher-librarians to meet the diverse educational, wellbeing, and recreational needs of our learning communities and to advocate for our value in an ever-changing information landscape.

Part B: Critical Evaluation

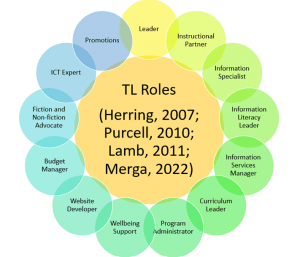

My very first assessment for this degree required me to reflect on my understanding of the role of teacher-librarians in schools (Lysaught, 2021a). For this task, I discussed the roles I focused on as part of my then-recent job application:

Little did I know, but this visual would serve as a prescient highlight to many of the issues explored throughout this course.

The early work completed in ETL401 introduced me to several roles expected of modern teacher-librarians, and as a result of my continued learnings in this degree I have consolidated these varied elements into three key themes.

Theme 1: Resourcing and Inspiring Reading for Pleasure

The first theme, resourcing and inspiring reading for pleasure, in many ways reinforces pre-existing stereotypes about the work of teacher-librarians as predominantly dealing with books. I discussed this misconception in my early blog posts, noting that these perceptions were largely based on community experiences (Lysaught, 2021a; Lysaught, 2021b). As a result of the readings and learning tasks in this degree, I have concluded that teacher-librarians must therefore ensure that we provide a multitude of different experiences to our communities to shape their perceptions of our roles as varied and valuable in an ever-changing modern information landscape.

However, Herring (2007, p.31) noted that fulfilling all the possible roles expected of teacher-librarians at one time is impossible. Anecdotal evidence suggests many teachers still don’t know what information literacy is, let alone a teacher-librarian’s role in developing student proficiency; those few who do often lack the time for collaborative planning and teaching. Rather than stress myself out by fighting an uphill battle and overhauling community perceptions completely, at the start of my teacher-librarian journey I’ve chosen to draw on my strengths as an English teacher and my pre-existing relationships with this faculty to lean into community expectations and show my value to our school by establishing a culture of pleasure reading. Once trust in my abilities as a teacher-librarian and strong relationships are formed through this Trojan horse, the plan is to leverage my success and branch out into other facets of my role, such as information specialist, to further entrench my value to our school community.

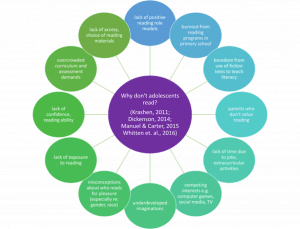

Step one in my plan to channel then subvert community expectations was to create a Wide Reading Program for the Stage 4 English classes. To show the value of this program to our school leaders, I aligned it with our Strategic Improvement Plan, foreshadowing the learnings of ETL504 Teacher Librarian as Leader. This program, inspired by the ETL402 Literature Across the Curriculum readings, aims to create a school-wide culture of pleasure reading. Reading for pleasure has repeatedly been shown to improve student literacies and socio-emotional development (Combes & Valli, 2007; Howard, 2011; Allington & Gabriel, 2012; Kid & Castano, 2013; Gaiman, 2013; Wu et al., 2013; Whitten et al., 2016; Ipri & Newman, 2017; Stower & Waring, 2018; Smith, 2019; Merga, 2021; Merga, 2022). Student reading drops off during adolescence for several reasons, including lack of access to quality texts, lack of positive reading role-models, lack of time, and lack of confidence in their reading ability:

This program aims to address these issues by providing students access to appropriate, self-selected texts and by setting aside a 60-minute period each fortnight to allow students time to explore, share, and value their reading in a socially supported positive learning environment (Gibson-Langford & Laycock, 2008; Krashen, 2011; Fisher & Frey, 2018; Merga & Mason, 2019; Allington & McGill-Franzen, 2021). Through this program I aim to create independent, lifelong readers who are set up for personal and academic success.

This initiative was first trialed in 2022, our first year without a school-wide DEAR program. It initially ran with 4 Year 7 classes which dropped back to 2 due to staffing issues and frequent interruptions. Data revealed that overall, the students who participated enjoyed the experience and found it beneficial, and I reported these findings to our Senior Executive via my Annual Library Report (Lysaught, 2023a):

In 2023 the Wide Reading Program was expanded from one teacher to six and now includes our Support Unit and two Year 8 classes, largely due to word of mouth and positive feedback from participating teachers – proving Bonanno’s (2011) argument that we should build relationships with the staff willing to work with us, since others will choose to follow once trust is developed (Crippen & Willows, 2019, p.173).

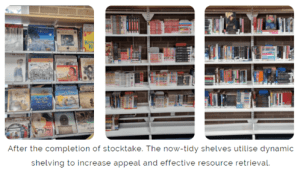

A crucial element of successfully inspiring reading for pleasure, especially amongst teens asserting their independence and exploring their identity, is the provision of relevant resources which support self-selection of reading materials (Beach et al., 2011; Allington & Gabriel, 2012; Fisher & Frey, 2018). To ensure a robust collection which meets the needs and interests of my patrons, I drew heavily upon the learnings gained in ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum. Library hygiene is an important element of ensuring an enticing, relevant collection (Fieldhouse & Marshall, 2011), and thus at the end of 2022 I completed a stocktake and significant weed of our Fiction and Quick Reads collections (Lysaught, 2023a). This was the first stocktake since 2018 and the median age of deselected resources was 1999, necessitating a serious update of our collection to ensure continued relevance. This was followed by subsequent stocktakes of our Picture Book and Graphic Novel collections at the start of 2023. Once these stocktakes were completed I introduced dynamic shelving to make the shelves more enticing and facilitate browsing (Bogan, 2022).

I also implemented patron-led acquisitions to increase circulation and user connection to the library’s resources (Hughes-Hassell & Mancall, 2005, p.9; Kimmel, 2014; Johnson, 2018; Aaron Cohen Associates, 2020, para.6; Crawford et. al, 2020, p.2), with 49% of newly acquired fiction resources specifically requested by staff and students in 2022 (Lysaught, 2023a). Drawing upon my experiences during my practicum, this year I bought 131 Hi-Lo books for our Quick Reads collection, and plan to use them for future Book Club activities during the Wide Reading lessons (Lysaught, 2023b). I am also in the process of genrefying our Quick Reads collection for easier browsing and selection, trialing the learnings gained in ETL505 Describing and Analysing Educational Resources (Lysaught, 2022a) in one of our popular, manageable collections.

Fisher & Frey (2018) argued that interventions designed to increase reading volume should rely on four factors: access, choice, classroom discussion of texts and book talks. The initiatives described above aimed to incorporate these four factors alongside efficient collection development and management. Loans statistics indicate that circulation has increased on the days when the Wide Reading lessons run, and as a result Oliver data shows we are on track to meet or beat our previous loans records since I became the teacher-librarian in 2020, despite our removal of a whole-school DEAR program in 2022.

Theme 2: Resourcing and Developing Reading for Information

As mentioned above, despite the importance of reading for pleasure in developing literacy, the role of a modern teacher-librarian should expand beyond the realm of books and into the crucial realm of information literacy to avoid the misunderstanding that our roles are limited and unnecessary in modern schools. I personally was guilty of this misconception prior to starting this degree, so I can hardly blame time-poor classroom teachers and senior leaders for not understanding our role, especially if they’ve never seen it in action! It is therefore necessary that we provide a variety of different experiences to our communities to shape their perceptions of our roles and ensure they understand our vital importance in developing our students as ethical, efficient users and creators of information. We cannot risk becoming an “invisible profession” (Valenza, 2010; Bonanno, 2011) and resourcing our libraries to develop information literacy is a path forward for teacher-librarians to show our value in a shifting infosphere increasingly filled with mis- and disinformation (Floridi, 2007, p.59; Lysaught, 2021c).

ASLA 2011. Karen Bonanno, Keynote speaker: A profession at the tipping point: Time to change the game plan from CSU-SIS Learning Centre on Vimeo.

The learnings gained in ETL401 Introduction to Teacher Librarianship were crucial in forcing me to revise my misunderstandings regarding the role of the modern teacher-librarian. For the second assessment I focused on how social media platforms affect our relationship with information, and discovered that improved internet access has changed information-seeking behaviours to favour passive information acquisition which uses the path of least resistance (often relying on social interactions), significantly impacting users’ ability to determine fact from fiction (Bates, 2010; Herbst, 2020; Liu, 2020; Kuhlthau et al., 2021). Teenagers are particularly likely to gain information from online, social sources and, far from being ‘digital natives’ equipped to navigate online information, are uniquely vulnerable to misinformation (Combes, 2009; Jacobson, 2010; O’Connell, 2012; Common Sense Media, 2019; Australian eSafety Commissioner, 2021). As a high-school teacher-librarian, I therefore have an ethical responsibility to ensure that my collections and programs equip my students with the skills and competencies they’ll need to be information literate in an increasingly digital world. Anecdotal evidence suggests that for many secondary classroom teachers, the fact that teacher-librarians don’t teach to a specific curriculum demeans our value. The recently released Information Fluency Framework (NSW Department of Education, 2023) offers an exciting way to legitimise our work moving forward, showcasing that we can be the glue which brings learning areas together, and will form the focus of my professional learning after finishing this degree. In the meantime I will continue to run one-off research skill lessons for my colleagues as requested.

Inquiry learning was another key aspect of our role explored in ETL401. While I had been familiar with concepts such as Project Based Learning from my time as a classroom teacher (Lysaught, 2021d), other methods such as Guided Inquiry Design were eye-opening and revealed a new pedagogy full of potential for my students (Lysaught, 2021e), since information literacy is foundational to inquiry learning (Fitzgerald, 2015). I greatly enjoyed reworking our existing Year 7 Shakespeare unit into a Guided Inquiry Design unit and look forward to the opportunity to co-teach it in future (Lysaught, via Guided Inquiry in Australia, 2020), alongside the digital narrative I created for ETL533.

ETL533 Assessment 4 – Digital Storytelling: A Day in Elizabethan England by Danielle Lysaught (Danielle Lysaught)

However, implementing inquiry learning and developing information literacy programs has not been without significant challenges in reality. Early on I identified that high staff workloads and minimal free time would likely hamper potential attempts to implement collaborative inquiry learning (Lysaught, 2021f). As such, there has been limited staff uptake. However, largely due to the relationships and trust developed through the Wide Reading Program, I have finally been asked to work with one of the English teachers and her Year 8 class in Term 4 on a unit exploring suspenseful narratives. The ETL512 Study Visits emphasised the importance of emotional intelligence and persistence as key traits for teacher-librarians, and my personal experience shows that we must be resilient in the face of setbacks and persist in the hope that we can eventually have the opportunity to showcase our value to our colleagues.

Effective collection management is another crucial aspect to developing information literacy in our community. ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum and ETL505 Describing and Analysing Educational Resources reinforced the importance of efficient resource management for supporting curriculum learning. In 2021 I completed a stocktake of our non-fiction collections – the first since 2018. The shelves were overflowing, messy, and not conducive to easy selection of relevant material:

Prior to this stocktake, the median date of publication was 1981. I weeded 2468 outdated or damaged resources, almost halving the collection and bringing the median date of publication to 2000 – an improvement, but indicating that there is still significant work to be completed to ensure a current, relevant collection which meets the needs of my staff and students. Foreshadowing the learnings of ETL504, I published the findings from this stocktake in my 2021 Annual Report and shared it with the Senior Executive to highlight the complexities of my role to our school leaders (Lysaught, 2022b).

In 2022 we started accessioning English novels to support their resource management, leading to it becoming our third largest collection:

This year, due to the success of this initiative, we have also had requests from the Science Faculty to assist with the management of their Stage 6 resources. While not without challenges, this provides a way for me to showcase my value to my colleagues, support curriculum learning through effective resource management, and interact with students who would otherwise possibly not utilise the library.

Theme 3: Promotion and Advocacy through Leadership

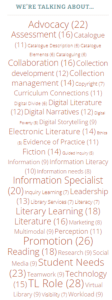

Two of the most used tags on my blog are ‘promotion’ and ‘advocacy’, so it’s only appropriate that the final theme discussed focuses on these issues.

Early in this degree the readings revealed the importance of advocating for our positions (Lysaught, 2021g), meaning that right from the start I’ve developed an awareness of the importance of perception and relationships in our role. This was consolidated throughout this degree in every unit.

In an early blog post for ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum I noted that, due to the teacher-librarian’s often poorly defined role and lack of clear curriculum direction, we are often utilised in different ways to support whatever the school requires (Lysaught, 2021h). It is therefore crucial for us to collaborate with our colleagues so that they understand our varied roles, ensuring our continued visibility and effectiveness to our school community. As seen through the frequent ‘promotion’ and ‘advocacy’ tags in my blog, so much of our work gives us the chance to increase our visibility; while it can be tempting to give up in the face of colleagues who view us as having the “cushy job”, we need to change our mindset and instead reframe challenges as “chopportunities” (Weisburg, 2020) and look for ways to make our work seen, valued, and understood (Valenza, 2010; Bonanno, 2011).

My final unit, ETL504 Teacher Librarian as Leader, emphasised the different leadership styles that we can leverage to maximise our effectiveness to our colleagues. Effective leadership, regardless of the approach or title, should focus on building strong relationships with others through mutual trust, respect, and effective communication (Holmes et al., 2012, p.271, 276; Moir et al., 2014, p.37; Ezard, 2015; Gleeson, 2016). My very first blog post had outlined my intent to support both staff and students (Lysaught, 2021i), and thus Servant Leadership appealed to me from the start (Lysaught, 2023c). In particular I was drawn to Servant Leadership due to its focus on empowering and developing others, humility, commitment to growth and community building, highly developed interpersonal skills, stewardship, healing, conceptualisation, and foresight (Arar & Oplatka, 2022, p.83-87; Crippen & Willows, 2019; p.171-172), and found that its guiding questions – ‘do you want to serve or be served?’ and ‘do those served grow as persons?’ (Blanchard & Broadwell, 2018; Greenleaf, 2008, p.36) – aligned well with my personal traits and values, and could help me support and heal cynical, time-poor staff and to act as mentors for both staff and students (Branch-Mueller & Rodger, 2022, p.46-47; Reinsel Soulen, 2020, p.39-40; Uther & Pickworth, 2014, p.21-23).

As a result of the learnings in this degree, I’ve experimented with a variety of different promotions and advocacy methods. I began this degree in mid-2021 when NSW started online learning followed by cohorting, which made collaboration and promotion particularly challenging early on; this has been further compounded by the current teacher shortage and high staff turnover at our school. Some of the early initiatives I implemented to raise the library’s profile include the Student Media Team, a Babble, Books and Breakfast club working alongside the Wellbeing faculty, and a Staff and Student Book Club (Lysaught, 2021j). While the book club fell apart due to lack of interest and time after online learning finished, the other two initiatives are still going strong. My early attempts at strategic planning appear quite amateurish in hindsight, though the alignment of my initiatives to our Strategic Improvement Plan and promotion of my work through Annual Reports foreshadowed the strategies suggested in ETL504 (Lysaught, 2023d). Our school recently experimented with the idea of holding all Stage 6 exams in the library, which if enacted would necessitate its closure for over 2 months of the school year. I was able to successfully leverage leadership strategies and use visitor and loans data collected each day to show the impact library closures would have on our school community, convincing the decision makers to choose another option:

Looking to the future, I will continue to experiment and expand on the learnings gained from this degree. First I will create a library operations folio to ensure effective management and strategic planning moving forward (Braxton, n.d.; National Library of New Zealand, n.d.; Oberg & Schultz-Jones, 2015). I was particularly inspired by the idea of hooking in new and current staff via mentoring (Cox & Korodaj, 2019; Reinsel Soulen, 2020), and building community ownership through a library committee has been a long-time goal of mine (Lysaught, 2021h). Inspired by ETL505 and the ETL512 study visits, I’d also love to create a library website to increase visibility and support teaching and learning by providing easily accessible pathfinders and research lessons. This journey is a marathon, not a sprint, and this degree has shown countless potential pathways to follow in future.

Part C Reflection

At the beginning of this course, we were asked to consider what makes a teacher-librarian (Lysaught, 2021a). My understanding of the role has expanded significantly since those early days:

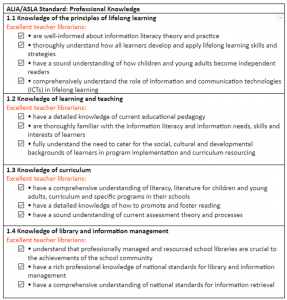

However, despite the complexity of our role, our work is still widely misunderstood. This degree has shown me that to be seen as professionals, we must act as professionals and take every opportunity to advocate for our role through the work we do in our school communities. The professional standards developed by the Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA) and the Australian School Library Association (ASLA) provide a useful framework for evaluating our professional practice and ensuring that we remain relevant and visible to our peers.

As a classroom teacher with experience teaching both the English and History syllabi from Year 7 through to Year 12, including the Extension courses for both subjects, I feel quite confident in my abilities as a teacher with strong professional and pedagogical knowledge who meets the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, many of which align with the ALIA/ASLA Standards through their similar professional domains (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2022). While I already had a strong understanding of reading practices, assessment, and ICT, this degree introduced me to the wonders of information literacy and collection management which have allowed me to be even more effective in my classroom practice and developed my understanding of how to support my colleagues more efficiently in my library role.

As a relatively new teacher-librarian, I feel that I still have a fair way to go regarding my professional practice, particularly regarding our role as information specialists. While I believe that I have created an environment where learners are encouraged to engage with our resources for understanding and enjoyment, I need to do more to ensure an information-rich learning environment which meets the needs of my community. I’ve worked hard over the last 2 years to build an environment which fosters positive wellbeing and strong reading culture, and due to these relationships and the trust I’ve developed with our teaching staff I’ve finally got the opportunity in Term 4 to collaboratively develop and teach a Guided Inquiry unit. Likewise, while I’ve previously done some strategic planning and budgeting (Lysaught, 2023d), the skills gained in this course will leave me much better equipped to plan for the future and ensure the library’s continued relevance and value to my school. In Term 4 I therefore intend to create a Library Operations Folio, including strategic and operations plans alongside policies for collection development, ICT use, and potential challenges.

I am already a member of several professional organisations, and fully intend to take advantage of their professional development. This will focus on the development and delivery of information literacy programs and wellbeing programs, broadening my understandings further and allowing me to showcase the potential in our practice to our wider school community.

Advocacy through action and alliances is my path forward in what could otherwise be an isolated, misunderstood role. While building my Wide Reading Program I have relied heavily on the action research process to ensure that my practice is evidence-based, innovative, and meets the needs of my staff and students. I have used this research to showcase my professionalism and the potential of my role to my colleagues, particularly to my school leaders. However, evaluating my work against the ALIA/ASLA standards shows that more could be done to develop my leadership capabilities. ETL504 emphasised the importance of leading from the middle by working with staff as well as students, such as through collaboratively teaching, leading professional development, or running key committees (Green, 2011; Wong; 2012; Wolf et al., 2014; Baker, 2016; Crippen & Willows, 2019; Reinsel Soulen, 2020). High staff turnover makes developing relationships with my colleagues a challenge, but also presents a ‘chopportunity’ (Weisburg, 2020) to exhibit both transformational and servant leadership, hook in new staff, and build a culture of library collaboration and appreciation from the ground up.

References:

Aaron Cohen Associates, ltd. (2020, October 23). Libraries provide ‘just in time’ expertise / ‘just in case’ resources. The Library Incubator: Library Consultant Web Site. https://www.acohen.com/blog/libraries-provide-just-in-case-experiences-just-in-time-access/

Allington, R. L., & Gabriel, R. E. (2012). Every child every day. Educational Leadership, 69(6), 10-15.

Allington, R. L., & McGill-Franzen, A. M. (2021). Reading Volume and Reading Achievement: A Review of Recent Research. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(1), S231–S238. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.404

Arar, K., & Oplatka, I. (2022). Advanced theories of educational leadership. Springer.

Australian eSafety Commissioner (2021). eSafety research: the digital lives of Aussie teens. https://www.esafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-02/The%20digital%20lives%20of%20Aussie%20teens.pdf

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL] (2022). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers.pdf

Baker, S. (2016). From teacher to school librarian leader and instructional partner: A proposed transformation framework for educators of preservice school librarians. School Libraries Worldwide, 22(1), 143-159. https://iasl-online.org/resources/Documents/PD%20Library/11bakerformattedfinalformatted143-158.pdf

Bates, M. J. (2010). Information Behavior. Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences, 3rd Ed. 2381-2391.

Beach, R., Appleman, D., Hynds, S., & Wilhelm, J. (2011). Teaching literature to adolescents. Taylor and Francis.

Blanchard, K., & Broadwell, R. (2018). Servant leadership in action.

Bogan, K. (2022, February 28). Dynamic shelving pt. 1: Introducing dynamic shelving. Don’t Shush Me! https://dontyoushushme.com/2022/02/28/embracing-dynamic-shelving/

Bonanno, K. (2011). A profession at the tipping point: Time to change the game plan. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/31003940

Branch-Mueller, J., & Rodger, J. (2022). Single Threads Woven Together in a Tapestry: Dispositions of Teacher-Librarian Leaders. School Libraries Worldwide, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.29173/slw8454

Braxton, B. (n.d.). Policies and procedures. 500 Hats: The Teacher Librarian in the 21st Century. https://500hats.edublogs.org/policies/

Combes, B., & Valli, R. (2007). Fiction and the twenty-first century: A new paradigm? Paper submitted to Cyberspace, D-world, e-learning. Giving schools and libraries the cutting edge, 2007 IASL Conference, Taipei, Taiwan.

Combes, B. (2009). Generation Y: are they really digital natives or more like digital refugees? Synergy 7(1), 31-40.

Common Sense Media (2019). The Common Sense census: media use by tweens and teens. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/2019-census-8-to-18-key-findings-updated.pdf

Cox, E. & Korodaj, L. (2019). Leading from the sweet spot: Embedding the library and the teacher librarian in your school community. Access, 33(4), 14-25.

Crawford, L. S., Condrey, C., Avery, E. F., & Enoch, T. (2020). Implementing a just-in-time collection development model in an academic library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 46(2), p.102101.

Crippen, C. & Willows, J. (2019). Connecting teacher leadership and servant leadership: A synergistic partnership. Journal of Leadership Education, 18(2), pp. 171-180.

Ezard, T. [BastowInstitute]. (2015, July 27). Building trust and collaboration – Tracey Ezard [Video]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/kUkseAdKyek

Fieldhouse, M., & Marshall, A. (2011). Collection development in the digital age. Facet.

Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2018). Raise reading volume through access, choice, discussion, and book talks. Reading Teacher, 72(1), 89-97. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1691

Fitzgerald, L. (2015a). Guided inquiry in practice. Scan 34(4), 16-27.

Floridi, L. (2007). A Look into the Future Impact of ICT on Our Lives. The Information Society 23(1), 59-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/019722406010599094

Gaiman, N. (2013, October 16). Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming

Gibson-Langford L., & Laycock D. (2008). The archery of reading. Access, 22(2), 9-13.

Gleeson, B. (2016, November 9). 10 unique perspectives on what makes a great leader. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brentgleeson/2016/11/09/10-unique-perspectives-on-what-makes-a-great-leader/#276777b95dd1

Green, G. (2011). Learning leadership through the school library. Access, 25(4), 22-26.

Greenleaf, R. K. (2008). Greenleaf on Servant-Leadership: Who Is the Servant-Leader? The International Journal of Servant-Leadership, 4(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.33972/ijsl.234

Guided Inquiry Oz (2020, March 3). Secondary guided inquiry units. https://guidedinquiryoz.edublogs.org/practice-2/secondary-guided-inquiry-units/

Herbst, M. (2020, January 27). How to Raise Media-Savvy Kids in the Digital Age. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/kids-digital-media-literacy-tips/

Herring, J. (2007). Teacher librarians and the school library. In S. Ferguson (Ed.) Libraries in the twenty-first century: charting new directions in information (pp. 27-42). Wagga Wagga, NSW : Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.

Holmes, K., Clement, J. & Albright, J. (2012). The complex task of leading educational change in schools. School Leadership & Management, 33(3), 270-283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2013.800477

Howard, V. (2011) the importance of pleasure reading in the lives of young teens: Self-identification, self-construction and self-awareness. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 43(1), 46-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000610390992

Hughes-Hassell, & S., Mancall, J. C. (2005). Collection management for youth: responding to the needs of learners. American Library Association.

Ipri, T., & Newman, B. (2017). Beginner’s guide to transliteracy: Where did the term transliteracy come from? Libraries and Transliteracy. https://librariesandtransliteracy.wordpress.com/beginners-guide-to-transliteracy/

Jacobson, H. F. (2010). Found it on the internet: Coming of age online. American Library Association.

Johnson, P. (2018). Fundamentals of collection development and management. ALA Editions.

Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science 342(6156), 377-380.

Kimmel, S. C. (2014). Developing collections to empower learners. American Library Association.

Krashen, S. D. (2011). Free voluntary reading. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Heinstrom, J., & Todd, R. J. (2008). The ‘information search process’ revisited: is the model still useful? Information Research, 13(4)

http://informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper355.html

Liu, F. (2020, January 26) How Information-Seeking Behavior Has Changed in 22 Years. Nielsen Norman Group.

https://www.nngroup.com/articles/information-seeking-behavior-changes/

Lysaught, D. (2021a, July 19). ETL401 assessment 1: What is the role of the teacher librarian? All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/07/19/etl401assessment1/

Lysaught, D. (2021b, August 29). ETL401 3.2 the role of the teacher librarian – LIBERating our perceptions. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/08/29/3-2-the-role-of-the-teacher-librarian-liberating-our-perceptions/

Lysaught, D. (2021c, August 30). ETL401 2.3 the information landscape. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/08/30/2-3-the-information-landscape/

Lysaught, D. (2021d, September 14). ETL401 5.4b convergence. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/09/14/5-4b-convergence/

Lysaught, D. (2021e, September 14). ETL401 5.4a information literacy. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/09/14/5-4a-information-literacy/

Lysaught, D. (2021f, September 7). ETL401 4.1 inquiry learning: Some thoughts. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/09/07/4-1-inquiry-learning-some-thoughts/

Lysaught, D. (2021g, August 29). ETL401 3.2 the role of the teacher librarian: An invisible profession? All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/08/29/3-2-the-role-of-the-teacher-librarian-an-invisible-profession/

Lysaught, D. (2021h, November 22). ETL503 2.1 developing collections. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/11/22/etl503-2-1-developing-collections/

Lysaught, D. (2021i, July 9). I’m going on an adventure!!!. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/07/09/hello-world/

Lysaught, D. (2021j, December 26). ETL402 3.1 strategies to leverage a love of reading. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2021/12/26/etl402-3-1-strategies-to-leverage-a-love-of-reading/

Lysaught, D. (2022a, July 4). ETL505 assessment 3 part c: Genrefication essay. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/07/04/etl505-assessment-3-part-c-genrefication-essay/

Lysaught, D. (2022b). 2021 Annual Library Report. https://www.canva.com/design/DAEwsCALUsI/vyQMXh9an6lLizamxaUW_Q/view?utm_content=DAEwsCALUsI&utm_campaign=designshare&utm_medium=link&utm_source=publishsharelink

Lysaught, D. (2023a). 2022 Annual Library Report. https://bit.ly/3Jg1e7k

Lysaught, D. (2023b, July 13). ETL512 assessment 5: Professional placement report. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2023/07/13/etl512-assessment-5-professional-placement-report/

Lysaught, D. (2023c, March 12). ETL504 2.2 leadership theory. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2023/03/12/etl504-2-2-leadership-theory/

Lysaught, D. (2023d, April 27). ETL504 strategic planning and setting goals: An amateur’s journey. All You Read Is Love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2023/04/27/etl504-strategic-planning-and-setting-goals-an-amateurs-journey/

Merga, M., & Mason, S. (2019). Building a school reading culture: Teacher librarians’ perceptions of enabling and constraining factors. Australian Journal of Education 63(2):173-189. DOI:10.1177/0004944119844544

Merga, M. (2021). Libraries as wellbeing supportive spaces in contemporary schools. Journal of Library Administration 61(6). DOI:10.1080/01930826.2021.1947056

Merga, M. (2022). School libraries supporting literacy and wellbeing. Facet.

Moir, S., Hattie, J. & Jansen, C. (2014). Teacher perspectives of ‘effective’ leadership in schools. Australian Educational Leader, 36(4), 36-40.

National Library of New Zealand. (n.d.). Getting started in your school library: An operations checklist. National Library: Services to schools. https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/school-libraries/library-systems-and-operations/library-operations/getting-started-in-your-school-library-an-operations-checklist

NSW Department of Education (2023). Information Fluency Framework. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/school-libraries/teaching-and-learning

Oberg, D., & Schultz-Jones, B. (eds.). (2015). Collection management policies and procedures. In IFLA School Library Guidelines, (2nd ed.), (pp. 33-34). Den Haag, Netherlands: IFLA.

O’Connell, J. (2012). So you think they can learn? Scan 31, 5-11.

Reinsel Soulen, R. (2020). The continuum of care. Knowledge Quest, 48(4). 36-42.

Smith, A. K. (2019, October 14). Literature has the power to change the world. Here’s how. Books At Work. https://www.booksatwork.org/literature-has-the-power-to-change-the-world-heres-how/

Stower, H. & Waring, P. (2018, July 16). Read like a girl: Establishing a vibrant community of passionate readers. Alliance of Girls Schools Australia. https://www.agsa.org.au/news/read-like-a-girl-establishing-a-vibrant-community-of-passionate-readers/

Uther, J., & Pickworth, M. (2014). TLs as leaders: are you a Highly Accomplished teacher librarian? Access, 28(1), 20–25.

Valenza, J. (2010, December 3). A revised manifesto. School Library Journal. https://blogs.slj.com/neverendingsearch/2010/12/03/a-revised-manifesto/

Weisburg, H. K. (2020). Leadership: There is no other option. Synergy, 18(1). https://slav.vic.edu.au/index.php/Synergy/article/view/369/364

Whitten, C., Labby, S., & Sullivan, S. L. (2016). The impact of pleasure reading on academic success. The Journal of Multidisciplinary Graduate Research 2(4), 48-64.

Wolf, M., Jones, R. & Gilbert, D. (2014). Leading in and beyond the library. http://all4ed.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/BeyondTheLibrary.pdf

Wong, T. (2012). Strategic long-range planning. Library Media Connection, 31(2), 22-23..

Wu, Y., Mallan, K., & McGillis, R. (2013). Reimagining the world: Children’s literature’s responses to changing times. Springer.