iPoe by iClassics Collection is a wonderful example of the second category of digital text defined by both Unsworth and Allan (Lysaught, 2022): an enhanced app or electronically augmented text.

Published across three volumes between 2012-2015 for Apple and Android devices, iPoe is a creative augmentation of several Edgar Allan Poe texts alongside contextual information and details about the app designing process. Each volume recontextualises Poe’s original texts alongside interactive illustrations, music, and sound effects which effectively utilise the multimodal and interactive potential of digital environments to enhance the reader’s experience and understanding. This resource would suit our Year 8 unit on suspenseful stories, therefore I’ll focus on two texts relevant to this unit: The Tell-Tale Heart (vol.1) and The Raven (vol.2).

Unsworth defines electronically augmented literary texts as those which take traditionally published print texts and augment them with digital resources to “enhance and extend” the original (2006, p.2). This can be through the addition of digital features such as interactivity and multimodality (Walsh, 2013, p.187) or supplementary digital resources designed to extend commentary, discussion, and interpretation of the text (Kitson, 2017, p.59). Arguably, iPoe features both. Allan (2017, p.22) defines narrative apps as digital, interactive remediations of print narratives – a category into which iPoe seems to fit nicely. However, as with my other reviews (Lysaught, 2022), looking at iPoe from different angles raises questions regarding definition and categorisation of digital texts. Much like the paradoxical ‘ship of Theseus’, I wonder how much has to be changed before it is considered a new, ‘born digital’ text in its own right, since the combination of iPoe’s multimodal and supplementary features greatly enhanced my experience of Poe’s stories, especially through the app’s original artwork and soundtrack. Furthermore, iPoe could fit Unsworth’s sub-category of a linear e-narrative digitally originating text (2006, p.3-4), since it presents an illustrated traditional, linear narrative on screen. Clearly defining digital literature is not so clear!

The interactive multimodal features of iPoe are testament to the transformative potential of literature in digital environments. The iClassics website claims 85 minutes of original soundtrack by Teo Grimalt and Miquel Tejada, 185 sound effects and 95 original interactive illustrations by David G. Forés (iClassics Productions, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c) – reflecting that ‘authorship’ in digital contexts is often shared (Bowler et al., 2012, p.43).

In The Raven, readers can touch the titular bird to hear it croak ‘Nevermore’, while their understanding of Gothic metonymy and atmosphere is enhanced through other sound effects such the knocking on the door, the fire’s crackling, the hinges creaking, and the wind’s howling. In one dramatic moment, touching the raven led to a shift in camera focus to the ponderous protagonist, while in another readers are invited to touch Lenore’s portrait; the subsequent cracking glass emphasised the protagonist’s fracturing mental state. Likewise, the penultimate image of the protagonist wavering alongside Lenore’s ephemeral ghost was a brilliant representation of grief.

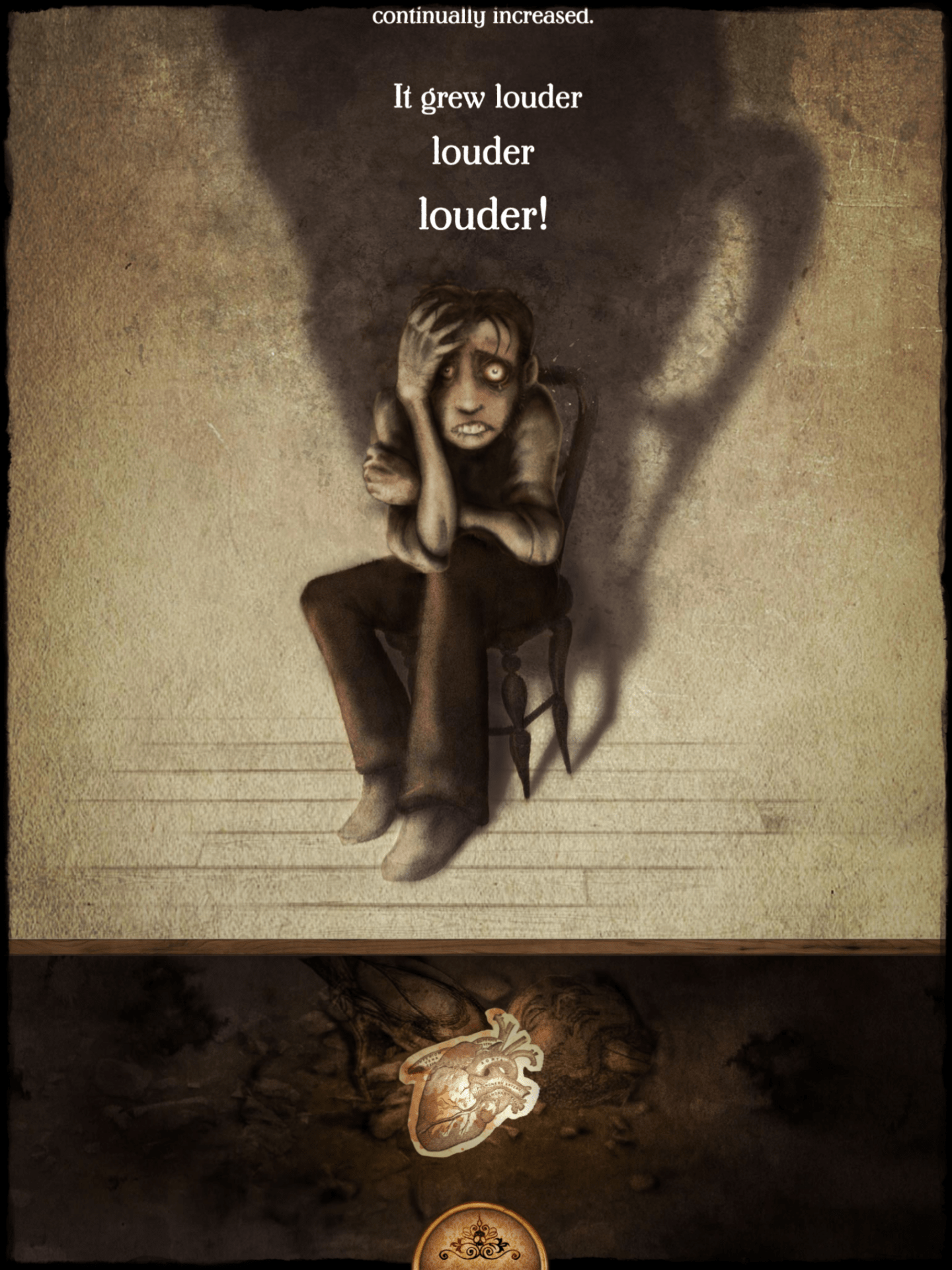

These multimodal features similarly enhanced my experience reading The Tell-Tale Heart. The old man’s eye shifted into a vulture’s, supplementing the written text with the visuals. The interactive image of the old man, shivering under the reader’s watchful gaze, accentuated his fragility and aligned the reader with the protagonist’s perspective, as did the dark page where text could only be partially illuminated by moving the reader’s finger. The masterful soundtrack underscored the climactic moment of murder through its overwhelming crescendo and fading heartbeat. I experienced genuine discomfort as I watched a dolly zoom of the protagonist murdering the old man before literally turning his gaze to me. The protagonist’s increasing paranoia was stressed with visuals and associated sound effects, particularly when I was invited to touch a close-up of his panicked eyes. His final admission of guilt was brought to life through these multimodal elements – when readers touch the still-beating heart, bloody fingerprints appear on the page.

Interactive, multimodal elements are supported by mobile features such as gyro-perspective, flash, and vibration ((iClassics Productions, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c), though I didn’t notice these to any great extent. Also, while some multimodal elements greatly enhanced my reading experience, others were distracting, such as the initial photo and the dismembered corpse in The Tell-Tale Heart. However, the contextual information amplified my understanding of Poe’s life, times, and works (James & Kock, 2013), p.108).

However, logistical issues around cost, access, and other required technology should also be considered when evaluating digital texts for school libraries (Lysaught, 2022a). The app bundle cost $8.99 on the Apple Store, expensive to replicate on 1:1 devices. Aural elements required additional headphones and were fiddly, while constant review pop-ups interrupted immersion. Also, I couldn’t adjust the font size or define unknown words – favoured features of digitised texts. Overall, I greatly enjoyed iPoe since it effectively utilised the multimodal and interactive potential of the digital format to enhance my understanding and engagement, especially compared with other gimmicky narrative apps such as Alice for the iPad (Lysaught, 2022b).

821 words.

Reference list:

Allan, C. (2017). Digital fiction: ‘Unruly object’ or literary artefact? English in Australia, 52(2), 21-27.

Bowler, L., Morris, R., Cheng, I-L., Al-Issa, R., Romine, B., & Leiberling, L. (2012). Multimodal stories: LIS students explore reading, literacy, and library service through the lens of “The 39 Clues”. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 53(1), 32-48.

iClassics Productions (2018a). Deliciously dark, devilishly fun. http://iclassicscollection.com/en/project/ipoe1/

iClassics Productions (2018b). Ravings of love & death. http://iclassicscollection.com/en/project/ipoe2/

iClassics Productions (2018c). The master of macabre returns. http://iclassicscollection.com/en/project/ipoe3/

James, R. & de Kock, L. (2013). The digital David and the Gutenberg Goliath: The rise of the enhanced e-book. English Academy Review: Southern African Journal of English Studies, 30(1), 107-123.

Kitson, L. (2017). Exploring opportunities for literary literacy with e-literature: To infinity and beyond. Australian Literacy Educators’ Association. Literacy Learning, 23(2), 58-68.

Lysaught, D. (2022a, August 14). ETL533 Evaluating Digital Literature: Deeper Considerations. All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/08/14/etl533-evaluating-digital-literature-deeper-considerations/

Lysaught, D. (2022b, August 13). ETL533 3.2: Exploring Digital Forms. All you read is love. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/allyoureadislove/2022/08/13/etl533-3-2-exploring-digital-forms/

Unsworth, L. (2006). E-literature for children: Enhancing digital literacy learning. Routledge.

Walsh, M. (2013). Literature in a digital environment (Ch. 13). In L. McDonald (Ed.), A literature companion for teachers. Marrickville, NSW: Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA).